Why Black History Month Matters in the UK

Every October, Black History Month serves as a vital period of reflection, education and celebration. It highlights the stories, achievements and contributions of African, Caribbean and diasporic communities that are too often overlooked in mainstream history. Established in 1987 through the efforts of Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, the month provides a platform to re-centre Black British identity, challenge historical silences, and inspire a deeper understanding of Britain’s diverse heritage. Today, it stands as a nationwide movement—embraced by schools, communities and institutions—to honour the past, celebrate the present and shape a more inclusive future.

BLACK HISTORY MONTH

✊🏿

BLACK HISTORY MONTH ✊🏿

Key Figures and Turning Points in UK Black History

Any teaching or praise of Black British history must go beyond a handful of names, but here are a few essential profiles and historical moments that illustrate the richness and struggle of Black lives in the UK:

Olaudah Equiano (c.1745–1797)

Born in what is now Nigeria and sold into slavery as a child, Equiano eventually purchased his freedom. Settling in London, he published The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789), which became one of the most influential slave narratives of its time. His writing propelled abolitionist sentiment in Britain and gave voice to lived experiences rarely heard in Parliament or in classrooms.

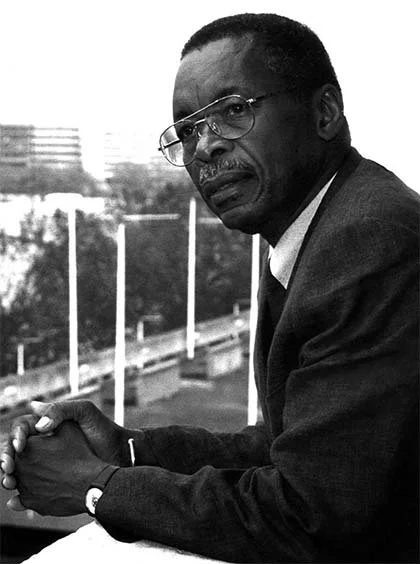

Len Garrison (1943–2003)

A seminal figure in the development of Black educational and archival activism, Len Garrison co-founded ACER (Afro-Caribbean Education Resource) and was instrumental in establishing the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton the UK’s first national centre dedicated to Black British life. His work insisted that Black histories belong to public memory and education, not just marginalised communities.

Mary Seacole (1805–1881)

Of Jamaican and Scottish descent, Mary Seacole travelled to the Crimean War and founded the “British Hotel” near the front lines, offering medical care, shelter, food and compassion to wounded soldiers. Her resourcefulness, cross-cultural medical practices and determination have made her a powerful symbol of care, resilience and agency beyond the confines of formal institutions.

Claudia Jones (1915–1964)

An influential journalist, political activist and thinker, Claudia Jones emigrated from Trinidad to the UK, where she fought for racial justice, women’s rights, and cultural recognition. She is credited with co-founding the precursor events that evolved into the Notting Hill Carnival, as a way of celebrating Caribbean culture and strengthening community resilience.

Important Dates & Moments

1823: Founding of the Society of the Rights of Man & the establishment of early abolitionist resistance in Britain, including petitions, speeches, and organized activism demanding abolition.

1833: The Slavery Abolition Act in the British colonies, followed by compensation to slave owners (not formerly enslaved people).1948: Arrival of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury, carrying Caribbean migrants who would become the Windrush Generation. A foundational chapter in modern Black British life.

1987: First UK Black History Month launch, marking emancipation anniversaries and the rising visibility of Black British identity.

2007: The centenary of the 1904–1905 transit of Black people into empire contexts, and the bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) received renewed public attention and some curricular inclusion of figures like Equiano began.

These names and events are not tokenism. They are emblematic of the broader currents of resistance, migration, contribution and cultural exchange that constitute British history and too often, parts of that history are obscured, skipped or simplified in school lessons.

Why Black History Month Is Important Beyond the Classroom

Black History Month is far more than a supplement to school syllabuses it is a vital moment in cultural, social and democratic life. It reminds us that the histories we choose to remember shape our identities, and in turn, shape power. When Black stories are excluded, it tells communities particularly young Black people that their ancestors, contributions and lived experiences are less worthy of recognition. This erasure has deep psychological, cultural and civic consequences, influencing who is seen as truly belonging, whose voices are valued, and how Britain’s national story is told.

At its core, Black History Month is a call to reflect on inequality, racism and justice not as relics of the past, but as ongoing realities. It creates space for honesty, acknowledgement and accountability, while amplifying stories and voices too often left unheard. Its visibility pushes schools, governments, media and cultural institutions into action commissioning exhibitions, hosting events, reshaping curricula and sparking conversations that ripple far beyond October. Yet its power depends on moving past tokenism; embedding Black history all year round is the only way to ensure the month drives systemic change rather than symbolic gestures.

Embedding Black History at the Heart of Education

The Black Curriculum’s mission goes beyond a single month of celebration — it is about embedding Black British history across the school year. By weaving it into history, literature, geography, art and citizenship, pupils gain a fuller understanding of how migration, empire, resistance and cultural exchange have shaped modern Britain. This is not just about representation, but about building historical literacy, critical thinking and social cohesion.

A curriculum that centres Black British lives challenges institutional amnesia and ensures all voices are valued. The Black Curriculum offers a proven model — through training, partnerships and tailored support — that equips schools to deliver inclusive, confident teaching. Black History Month may spark the conversation, but lasting change means embedding this history all year round. Every child in the UK deserves to see the lives, struggles and achievements that shaped this nation reflected in their education.